Writing in painting

If writing is used to tell stories and communicate ideas then painting is the oldest form of writing. The cave paintings are a form of narrative, the text for religious narrative and the earliest form, in the blown handprints of writing “Ug was here”. The cave paintings are symbols representing real living things.

Perhaps one of the greatest early example of painting as narrative is The Shaft Scene at Lascaux. This arrangement, made famous by its narrative potential, is one of the rare examples in which the subjects and themes refer to a specific episode.(Aujoulat)

Figure 01 The Shaft scene at Lascaux

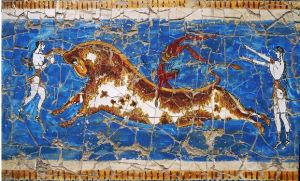

The Minoans continued the narrative theme with the wall painting Bull Jumping a composition that would not look out of place in a Manga or Marvel comic with speech and thought bubbles added.

Figure 02 Bull Jumping at Knossos

Then it was the turn of the Egyptians, who, through their rigid set of rules for painting turned the image into writing. The painted hieroglyphs became the words to accompany the images.

For the Christians the word was all powerful and the image was relegated to a supporting role until the dawn of the Renaissance when the narrative was concluded in the image, then for 200 years or so, almost the only word to appear in paintings was INRI.

Figure 03 Detail from Grunewald’s Crucifixion

Lautrec and Mucha made extensive use of graphics but theirs was poster art where words were necessary to inform the viewer of the event.

Apart from that instance, words then disappeared from paintings until Picasso and Braque brought them back as a way of preventing their cubist works from descending into abstraction.

The Dada artists were fond of words in their images, the surrealists less so Magritte’s Ce n’est pas un pipe, Duchamp’s R Mutt and LQOOH are the only examples I can think of until the advent of Lichtenstein’s pop art, whose speech and thought bubbles and onomatopoeic sounds were reminiscent of the comics. and then of course there was Warhol.

Joseph Kosuth and Ed Ruscha used text in their works in a very surrealist way, Banksy uses it in a political way and Samsudin Wahab is highly political in his use of text, but perhaps also uses it to tie his work to the newspaper inspiration from whence it springs.

I had a flick through Vitamin P2 and was quite surprised to discover that only thirteen of a hundred and fifteen artists included text in the featured works.

Do I use it, not really, I have used it in the past as part titles of newspapers when I was experimenting with cubism and I used it a little when I did a series of paintings on shop fronts but as a general rule I avoid it. I think it draws the eye too much, when it is necessary such as on a wine bottle label I prefer marks that look like writing from a distance but disappear into squiggles when you get close up, in much the same way that Annie Albers used it in her weaving. I don’t even sign my paintings on the front as I think the signature has the same effect. While we are speaking of words, I am not very keen on giving titles to my paintings other than short descriptive ones to distinguish one from the other words seem to limit the attention of the viewer, once you have found the words you think you understand and move on perhaps a better way is a brand symbol the way Basquiat used the three pointed crown.

One of my pet hates is writing on the walls of museums and galleries at exhibitions, the next time you go to a gallery look how people crowd around the words at the beginning of each room compared to how quickly they pass by the works on show. You can read the catalogue before you go or after you have been, just bathe your eyes on the works on show it could be half a lifetime before you see them again, there will be words on your phone when you switch it back on again.

Bibliography

Anjoulat, N. (s.d.) Lascaux: The Shaft. At: http://archeologie.culture.fr/lascaux/en/mediatheque/shaft (Accessed 16/01/19)